Let’s construct an internet web page in Swift. Discover ways to use the model new template engine of the most well-liked server facet Swift framework.

Undertaking setup

Begin a model new challenge by utilizing the Vapor toolbox. Should you don’t know what’s the toolbox or the right way to set up it, it’s best to learn my newbie’s information about Vapor 4 first.

// swift-tools-version:5.3

import PackageDescription

let package deal = Package deal(

identify: "myProject",

platforms: [

.macOS(.v10_15)

],

dependencies: [

// 💧 A server-side Swift web framework.

.package(url: " from: "4.32.0"),

.package(url: " .exact("4.0.0-tau.1")),

.package(url: " .exact("1.0.0-tau.1.1")),

],

targets: [

.target(name: "App", dependencies: [

.product(name: "Leaf", package: "leaf"),

.product(name: "Vapor", package: "vapor"),

]),

.goal(identify: "Run", dependencies: ["App"]),

.testTarget(identify: "AppTests", dependencies: [

.target(name: "App"),

.product(name: "XCTVapor", package: "vapor"),

])

]

)

Open the challenge by double clicking the Package deal.swift file. Xcode will obtain all of the required package deal dependencies first, then you definately’ll be able to run your app (you may need to pick the Run goal & the correct machine) and write some server facet Swift code.

Getting began with Leaf 4

Leaf is a robust templating language with Swift-inspired syntax. You need to use it to generate dynamic HTML pages for a front-end web site or generate wealthy emails to ship from an API.

Should you select a domain-specific language (DSL) for writing type-safe HTML (comparable to Plot) you’ll must rebuild your complete backend software if you wish to change your templates. Leaf is a dynamic template engine, this implies that you may change templates on the fly with out recompiling your Swift codebase. Let me present you the right way to setup Leaf.

import Vapor

import Leaf

public func configure(_ app: Utility) throws {

app.middleware.use(FileMiddleware(publicDirectory: app.listing.publicDirectory))

if !app.surroundings.isRelease {

LeafRenderer.Choice.caching = .bypass

}

app.views.use(.leaf)

strive routes(app)

}

With only a few traces of code you might be prepared to make use of Leaf. Should you construct & run your app you’ll be capable of modify your templates and see the modifications immediately if reload your browser, that’s as a result of we’ve bypassed the cache mechanism utilizing the LeafRenderer.Choice.caching property. Should you construct your backend software in launch mode the Leaf cache might be enabled, so you have to restart your server after you edit a template.

Your templates ought to have a .leaf extension and they need to be positioned beneath the Sources/Views folder inside your working listing by default. You’ll be able to change this conduct by the LeafEngine.rootDirectory configuration and you may also alter the default file extension with the assistance of the NIOLeafFiles supply object.

import Vapor

import Leaf

public func configure(_ app: Utility) throws {

app.middleware.use(FileMiddleware(publicDirectory: app.listing.publicDirectory))

if !app.surroundings.isRelease {

LeafRenderer.Choice.caching = .bypass

}

let detected = LeafEngine.rootDirectory ?? app.listing.viewsDirectory

LeafEngine.rootDirectory = detected

LeafEngine.sources = .singleSource(NIOLeafFiles(fileio: app.fileio,

limits: .default,

sandboxDirectory: detected,

viewDirectory: detected,

defaultExtension: "html"))

app.views.use(.leaf)

strive routes(app)

}

The LeafEngine makes use of sources to lookup template areas if you name your render operate with a given template identify. You too can use a number of areas or construct your personal lookup supply should you implement the LeafSource protocol if wanted.

import Vapor

import Leaf

public func configure(_ app: Utility) throws {

app.middleware.use(FileMiddleware(publicDirectory: app.listing.publicDirectory))

if !app.surroundings.isRelease {

LeafRenderer.Choice.caching = .bypass

}

let detected = LeafEngine.rootDirectory ?? app.listing.viewsDirectory

LeafEngine.rootDirectory = detected

let defaultSource = NIOLeafFiles(fileio: app.fileio,

limits: .default,

sandboxDirectory: detected,

viewDirectory: detected,

defaultExtension: "leaf")

let customSource = CustomSource()

let multipleSources = LeafSources()

strive multipleSources.register(utilizing: defaultSource)

strive multipleSources.register(supply: "custom-source-key", utilizing: customSource)

LeafEngine.sources = multipleSources

app.views.use(.leaf)

strive routes(app)

}

struct CustomSource: LeafSource {

func file(template: String, escape: Bool, on eventLoop: EventLoop) -> EventLoopFuture {

/// Your {custom} lookup technique comes right here...

return eventLoop.future(error: LeafError(.noTemplateExists(template)))

}

}

Anyway, this can be a extra superior subject, we’re good to go together with a single supply, additionally I extremely suggest utilizing a .html extension as an alternative of leaf, so Xcode can provide us partial syntax spotlight for our Leaf recordsdata. Now we’re going to make our very first Leaf template file. 🍃

You’ll be able to allow fundamental syntax highlighting for .leaf recordsdata in Xcode by selecting the Editor ▸ Syntax Coloring ▸ HTML menu merchandise. Sadly should you shut Xcode you need to do that time and again for each single Leaf file.

Create a brand new file beneath the Sources/Views listing known as index.html.

#(title)

Leaf offers you the flexibility to place particular constructing blocks into your HTML code. These blocks (or tags) are at all times beginning with the # image. You’ll be able to consider these as preprocessor macros (if you’re acquainted with these). The Leaf renderer will course of the template file and print the #() placeholders with precise values. On this case each the physique and the title secret’s a placeholder for a context variable. We’re going to set these up utilizing Swift. 😉

After the template file has been processed it’ll be rendered as a HTML output string. Let me present you ways this works in apply. First we have to reply some HTTP request, we are able to use a router to register a handler operate, then we inform our template engine to render a template file, we ship this rendered HTML string with the suitable Content material-Kind HTTP header worth as a response, all of this occurs beneath the hood routinely, we simply want to jot down just a few traces of Swift code.

import Vapor

import Leaf

func routes(_ app: Utility) throws {

app.get { req in

req.leaf.render(template: "index", context: [

"title": "Hi",

"body": "Hello world!"

])

}

}

The snippet above goes to your routes.swift file. Routing is all about responding to HTTP requests. On this instance utilizing the .get you’ll be able to reply to the / path. In different phrases should you run the app and enter into your browser, it’s best to be capable of see the rendered view as a response.

The primary parameter of the render technique is the identify of the template file (with out the file extension). As a second parameter you’ll be able to go something that may symbolize a context variable. That is often in a key-value format, and you should use virtually each native Swift sort together with arrays and dictionaries. 🤓

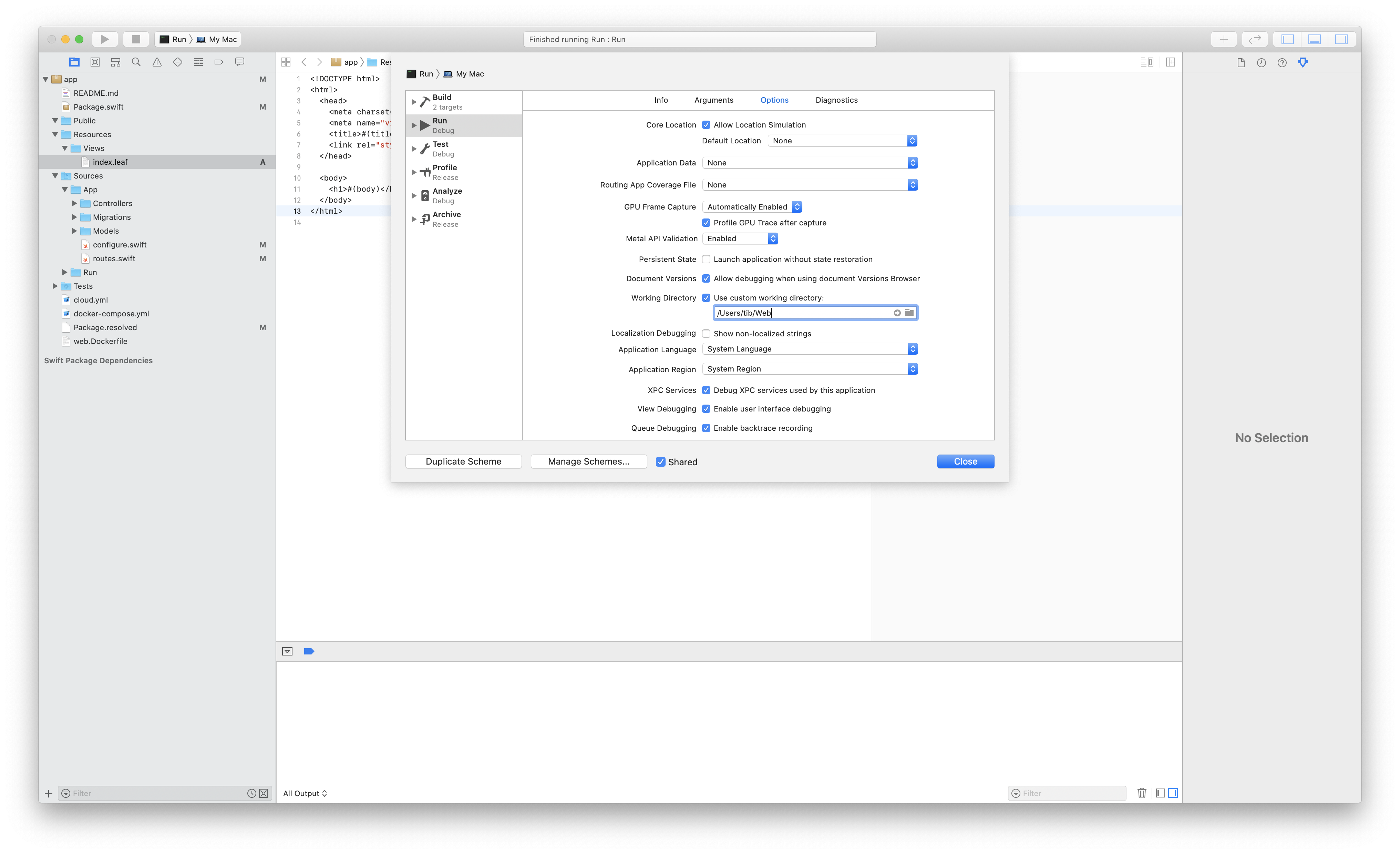

Once you run the app utilizing Xcode, don’t overlook to set a {custom} working listing, in any other case Leaf received’t discover your templates. You too can run the server utilizing the command line: swift run Run.

Congratulations! You simply made your very first webpage. 🎉

Inlining, analysis and block definitions

Leaf is a light-weight, however very highly effective template engine. Should you study the essential ideas, you’ll be capable of fully separate the view layer from the enterprise logic. In case you are acquainted with HTML, you’ll discover that Leaf is straightforward to study & use. I’ll present you some useful ideas actual fast.

Splitting up templates goes to be important if you’re planning to construct a multi-page web site. You’ll be able to create reusable leaf templates as elements that you may inline afterward.

We’re going to replace our index template and provides a possibility for different templates to set a {custom} title & description variable and outline a bodyBlock that we are able to consider (or name) contained in the index template. Don’t fear, you’ll perceive this whole factor if you take a look at the ultimate code.

#(title)

#bodyBlock()

The instance above is a very good start line. We may render the index template and go the title & description properties utilizing Swift, after all the bodyBlock can be nonetheless lacking, however let me present you ways can we outline that utilizing a special Leaf file known as residence.html.

#let(description = "That is the outline of our residence web page.")

#outline(bodyBlock):

#(header)

#(message)

#enddefine

#inline("index")

Our residence template begins with a relentless declaration utilizing the #let syntax (you may also use #var to outline variables), then within the subsequent line we construct a brand new reusable block with a multi-line content material. Contained in the physique we are able to additionally print out variables mixed with HTML code, each single context variable can be accessible inside definition blocks. Within the final line we inform the system that it ought to inline the contents of our index template. Because of this we’re actually copy & paste the contents of that file right here. Consider it like this:

#let(description = "That is the outline of our residence web page.")

#outline(bodyBlock):

#(header)

#(message)

#enddefine

#(title)

#bodyBlock()

As you’ll be able to see we nonetheless want values for the title, header and message variables. We don’t must cope with the bodyBlock anymore, the renderer will consider that block and easily change the contents of the block with the outlined physique, that is how one can think about the template earlier than the variable substitute:

#let(description = "That is the outline of our residence web page.")

#(title)

#(header)

#(message)

Now that’s not essentially the most correct illustration of how the LeafRenderer works, however I hope that it’ll allow you to to know this entire outline / consider syntax factor.

You too can use the

#considertag as an alternative of calling the block (bodyBlock()vs#consider(bodyBlock), these two snippets are basically the identical).

It’s time to render the web page template. Once more, we don’t must cope with the bodyBlock, because it’s already outlined within the residence template, the outline worth additionally exists, as a result of we created a brand new fixed utilizing the #let tag. We solely must go across the title, header and message keys with correct values as context variables for the renderer.

app.get { req in

req.leaf.render(template: "residence", context: [

"title": "My Page",

"header": "This is my own page.",

"message": "Welcome to my page!"

])

}

It’s attainable to inline a number of Leaf recordsdata, so for instance you’ll be able to create a hierarchy of templates comparable to: index ▸ web page ▸ welcome, simply observe the identical sample that I launched above. Price to say that you may inline recordsdata as uncooked recordsdata (#inline("my-file", as: uncooked)), however this manner they received’t be processed throughout rendering. 😊

LeafData, loops and situations

Spending some {custom} knowledge to the view will not be that tough, you simply have to evolve to the LeafDataRepresentable protocol. Let’s construct a brand new listing.html template first, so I can present you just a few different sensible issues as properly.

#let(title = "My {custom} listing")

#let(description = "That is the outline of our listing web page.")

#var(heading = nil)

#outline(bodyBlock):

#for(todo in todos):

- #if(todo.isCompleted):✅#else:❌#endif #(todo.identify)

#endfor

#enddefine

#inline("index")

We declare two constants so we don’t must go across the title and outline utilizing the identical keys as context variables. Subsequent we use the variable syntax to override our heading and set it to a 0 worth, we’re doing this so I can present you that we are able to use the coalescing (??) operator to chain optionally available values. Subsequent we use the #for block to iterate by our listing. The todos variable might be a context variable that we setup utilizing Swift afterward. We will additionally use situations to test values or expressions, the syntax is just about simple.

Now we simply must create a knowledge construction to symbolize our Todo gadgets.

import Vapor

import Leaf

struct Todo {

let identify: String

let isCompleted: Bool

}

extension Todo: LeafDataRepresentable {

var leafData: LeafData {

.dictionary([

"name": name,

"isCompleted": isCompleted,

])

}

}

I made a brand new Todo struct and prolonged it so it may be used as a LeafData worth throughout the template rendering course of. You’ll be able to prolong Fluent fashions identical to this, often you’ll have to return a LeafData.dictionary sort together with your object properties as particular values beneath given keys. You’ll be able to prolong the dictionary with computed properties, however this can be a nice approach to cover delicate knowledge from the views. Simply fully ignore the password fields. 😅

Time to render a listing of todos, that is one attainable strategy:

func routes(_ app: Utility) throws {

app.get { req -> EventLoopFuture in

let todos = [

Todo(name: "Update Leaf 4 articles", isCompleted: true),

Todo(name: "Write a brand new article", isCompleted: false),

Todo(name: "Fix a bug", isCompleted: true),

Todo(name: "Have fun", isCompleted: true),

Todo(name: "Sleep more", isCompleted: false),

]

return req.leaf.render(template: "listing", context: [

"heading": "Lorem ipsum",

"todos": .array(todos),

])

}

}

The one distinction is that now we have to be extra specific about varieties. Because of this now we have to inform the Swift compiler that the request handler operate returns a generic EventLoopFuture object with an related View sort. The Leaf renderer works asynchronously in order that’s why now we have to work with a future worth right here. Should you don’t how how they work, please examine them, futures and guarantees are fairly important constructing blocks in Vapor.

The very very last thing I need to discuss is the context argument. We return a [String: LeafData] sort, that’s why now we have to place an extra .array initializer across the todos variable so the renderer will know the precise sort right here. Now should you run the app it’s best to be capable of see our todos.

Abstract

I hope that this tutorial will allow you to to construct higher templates utilizing Leaf. Should you perceive the essential constructing blocks, comparable to inlines, definitions and evaluations, it’s going to be very easy to compose your template hierarchies. If you wish to study extra about Leaf or Vapor it’s best to test for extra tutorials within the articles part or you should purchase my Sensible Server Aspect Swift guide.